For my Papa, Wray Straus

When I was a little girl, I remember visiting my Papa’s house, each time greeted by the usual scent of mothballs and dampness, the kind of dampness that comes with living on the “wet side” of Waimea, the side that often gets caught in fog and rain. Whenever I catch a whiff of these familiar scents, I am transported back to his living room: sitting on antique rocking chairs and couches, surrounded by shelves and glass cases filled with things to be seen and not touched. As a young child, his living space seemed part home, part museum. Every wall featured something different: my grandmother’s lei hulu, her collection of hats made of woven lauhala, the feather cloak she started and finished with tiny red and yellow feathers. On the shelves were hula instruments, some wrapped in plastic to maintain their features, alongside an assortment of koa bowls and stone tools. While these areas of the house intrigued me, they were also familiar, full with things I had reference points for, or things that I could understand both in and out of context.

This was not the case for all the areas of his home, however. The bottom room, the room that was once a garage and later converted into a separate, enclosed space, was different and it was because of its difference that I was often drawn to it. Descending the stairs, I always felt somewhat like a tourist entering unfamiliar territory, one with new expectations and protocols. The walls were decorated with pictures, figures, and images that I could not “read.” I did not have the cultural knowledge to know where they came from: patterns of shells and sticks; hanging arrangements of braided fibers and carved wooden sea creatures; baskets and ornaments that I had no context for, other than their existence in my Papa’s house. It was in this space that my earliest inquires and curiosities about the larger Pacific were formed through both scent and story.

In the late 1970s, before retiring from the Honolulu Police Department, my Papa was chosen to be part of a small group of officers sent to the four island states of the Federated States of Micronesia: Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae. My Papa was assigned to Yap, and as he once explained, was directed there to “teach the Micronesian people, or Micronesian officers, police work.” Therefore, after packing, he and my grandmother made the journey to Yap, embarking on what he once lovingly referred to as “the most terrific adventure.” Their children, my mom and her siblings, were for the most part already grown and some had already started their own families. Therefore, this was their time, their move, the chance for the two of them to embark on their own journey.

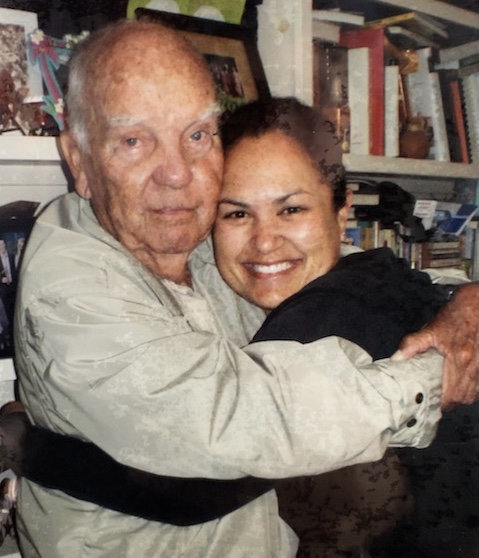

A few years ago, when he was 91, I sat with my Papa and asked him about his time in the region known as Micronesia. Seated in my mom’s house, wearing in his favorite beige jacket, holding a cup of strong black coffee in his hand, he recalled the little things, the things that made him and my grandmother laugh and smile: wearing slippers (what other islanders may call jandals) in the rain while trying to avoid red spots of betel nut on the wet earth; cooking with local ingredients and finding ways to bring the tastes of Hawaiʻi to a new place; and observing customs or protocols around seating arrangements and public acknowledgments that indicated who was of higher rank in the community. After spending two years in Yap, from 1977-1979, he was later stationed in Pohnpei, from 1980-1981, where they continued to make friends, to work, and to explore.

Today I think about my Papa’s explorations, his movements to other parts of the Pacific, and I realize that, in my own way, I’ve always been following him. Nearly three years ago, when I told my Dad that I was going to move back to Aotearoa, when I told him I was going to once again pack up my things and leave the shores of Hawaiʻi, he paused, took a deep breath, and said, “You were always the one to travel.” That willingness to physically depart my home, though, or that willingness to leave in order to arrive at parts of myself, my history, and my responsibilities to the region—that came from Papa. Growing up, we as grandkids were so accustomed to him always being there, in Waimea, with all of us, that we often forgot—until we sat in his house surrounded by carved and woven memories from Yap and Pohnpei—that he had an entire life before us.

After recording some of my Papa’s stories a few years ago, my intention was always to record more of them, to sit with him again to ask him to tell me more about the places and peoples that he loved dearly. It was always my intention to take his recorded memories, to put them alongside my grandmother’s letters home, and to (re)construct a narrative with him. Though I never did get the chance to sit with him again, to ask questions, and to record his answers, I do have that first interview and will treasure the chance I now have to revisit it, to hear his voice, to remember his travels, and to celebrate him over and over again.

Even while I now sit with his stories, listening to the recording, missing his deep and soothing voice, the many, complex layers of his travels are not lost on me. When he and my grandmother first went to Yap, they were two Hawaiians sent to live on another Pacific Island, sometimes seen as Americans and sometimes as fellow island people. Their descriptions of the people, places, and cultures they lived in and among were often framed by their own cultural upbringings in Hawaiʻi. At the same time, though, as both of my grandparents were born in 1927, they grew up knowing of their homeland as a territory of the United States and later as a “state” and were therefore sometimes influenced by imperial ideologies. Thus, their words were sometimes reinforcing of colonial power and at other times romantic, even while they were deeply appreciative and relational. While I will eventually dig into these complexities at another time, and in another piece, today my reflection is simply about Papa and about how he encouraged me to love the Pacific region through story before I was even aware of how that love would feed and guide my life.

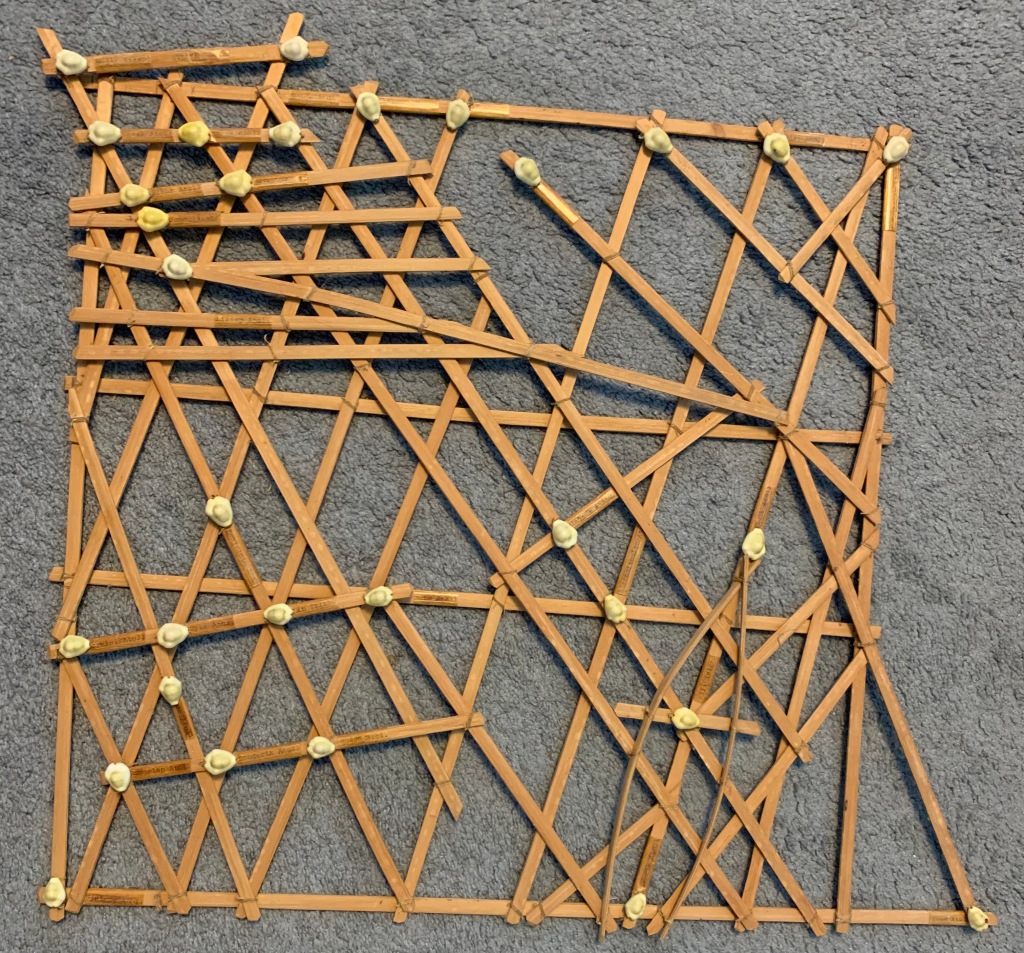

I was born after my Papa relocated back to Hawaiʻi, after my grandmother made her way to the realm of our ancestors, and after their travels in Micronesia were remembered in memories hung on the walls and suspended from the ceiling of their home. Among the items they brought back with them were a series of maps. As a little girl, I did not see them as such. They were unlike the “usual” paper-based maps used in my elementary school, those that placed the United States at the center and positioned Hawaiʻi in a box, floating somewhere off the coast of the so-called “mainland,” appearing rootless. These “maps” were disorienting. The stick charts in my grandfather’s house, on the other hand, were different: they were made of pieces of wood and shells, each one placed together with purpose, each one indicating direction. Before I realized what they were, I used to stare at them, thinking they resembled a constellation of sorts, like stars that could be traced together in lines of meaning. Each stick and shell intersected with another in a way that, although undecipherable to me, somehow seemed to make sense.

Years later, I saw a similar map hanging on the wall of an office at Vaʻaomanū Pasifika, the home of the Pacific Studies and Samoan Studies programs at Victoria University of Wellington. It took me back to mothballs and dampened carpets, to my Papa’s memories of betel nut and rain-drenched mornings. This particular map, a Marshallese rebbelib, or navigational chart, featured a series of sticks and small shells, “representing distinct islands, connected by ocean currents” (Teaiwa, 2017, 270). It belonged to my PhD supervisor—a charter of courses, a mapper of dreams, a navigator of “Pacific (Studies) Waters”—Teresia Teaiwa. Although I regrettably never shared this with her, and even though it came from a place that I had never been to myself (one I cannot and will not claim in any way), the map on her wall (a gift from her mother) reminded me of home. It was my connection to my Papa whose house was then (and is now, once again) over 4,000 miles away. In many ways, it was my reference point, and in others, it was a chart guiding my ever expanding and always evolving relationship with the Pacific.

Reflecting on the lives of these two people, my Papa and Teresia, two people who never met, but who each guided my life in different ways, with courses charted in sticks and shells—one who took his last earthly breath just yesterday and the other who left just five days shy of exactly four years ago as I write this—I feel obligated to honor the ways their travels, their journeys, and their lessons have brought me here. Today I was supposed to teach a class. I was supposed to give a lecture in a class that Teresia created, one that I now run myself. I had planned to talk about what it means to have a “sense of place,” a sense of belonging and attachment, or sense of responsibility for the Pacific, or for at least a piece of it. I was supposed to talk about how learning to love one part of the Pacific, even if the part of the Pacific we live in is not the part of the region we feel most attached to, is essential if we are ever going to feel obligated to protect our entire sea of islands. Today I was going to talk about connection.

But I felt too disconnected to do so.

With my body here Aoteaora and my head and heart in my Papa’s house at home, I decided I couldn’t do it today. So I made other arrangements for my students, walked home from work, and decided to write instead. I decided to write myself into, through, and even around the grief, even while it grips at me and I try to navigate the unfamiliarity of not being home with my family while they gather, mourn, plan, share food, share stories, and reminisce. Today, I decided to write about Papa. I decided to write his story and in doing so, I realized that one of the most profound lessons he taught me, a lesson that I will take back to my students, is that our sense of place, and perhaps most importantly, our ability to appreciate and love both the places we know and the places we don’t know, comes through our relationships with people. I’ve never been to Micronesia. I’ve never been to Yap or to Pohnpei. But they hold special places in my heart because of the ways they held my Papa for the years he was there, for the ways they embraced my grandmother, for the ways they taught them about themselves while away from home.

One of the challenges of being a Pacific Studies teacher is that, as Teresia once reflected, “Pacific studies is literally oceanic in its proportions” (267). “With over 1,200 indigenous languages—one-fifth of the contemporary world’s linguistic and cultural diversity—” she said, “the region commonly known as the Pacific Islands is so huge and so varied, and the pedagogical tasks consequently so complex, that the notion of a single, all-knowing teacher delivering knowledge from the front of the classroom is ludicrous” (266). What Teresia realized in her teaching, and what I’ve also come to embrace in my own, is that while we cannot take our students to the wider Pacific, taking them to all of those twenty thousand islands, we can start where we are and build meaning, understanding, and a love for the Pacific on the grounds beneath our feet. We can start through sharing stories in and of place to reacquaint ourselves with the memories we each hold of places and peoples, past and present. Though it sounds simple, I believe that students actually have to tap into remembering and actively calling upon their own sense of place and belonging—thinking about where they most feel at home, comfortable, held, or even heartbroken—to realize that our protective action for the entire region is to ensure that current and future generations of Pacific peoples have the same opportunity to create memories in their own place: to feel at home, to feel comfortable, and to feel held, even if and when those feelings come with heartbreak.

When I think about my Papa’s house, I realize that he taught me through the stories and travels that didn’t involve me, that occurred before I was born. He instilled in me an awareness for the region, even when it was beyond the familiar, even when I had no other reference points for it. He taught me that other places have meaning, have agency, and have importance independent of us. He taught me that other places deserve protection and justice and our active engagement. He taught me that in order to fight for the Pacific I have to first love it, in sight, in story, and in smell, even if that smell comes in the form of mothballs and dampness in an old Waimea house.

Today I miss that house, that smell, that feeling of being home and finding home in his voice, his laugh, and his smile. But, in reflecting on how he always encouraged my travels, always nurtured my curiosity, and always supported my ambitions—even when they took me far away from home—I know that at least one way to honor him is to tell his story, to bring you into the Pacific that he hung on his walls and kept in his heart, the Pacific that now feeds me and everything I do.

This is for you, Papa. This is for us. Mahalo.

References:

Teaiwa, Teresia. 2017. “Charting Pacific (Studies) Waters: Evidence of Teaching and Learning.” The Contemporary Pacific 29 (2): 265–82.