The following speech was delivered at ʻĀlana, the first benefit gala for Kanu o ka ʻĀina, a Hawaiian-focused charter school located in my hometown of Waimea on the Big Island of Hawaiʻi. I was invited to come home last Friday, 28 October 2016, to offer some “inspirational words.” Therefore, since graduating from the school 15 years ago, I decided to share what it has come to mean, at least for me, to be a Kanu o ka ʻĀina, a native of the land, in the 21st century.

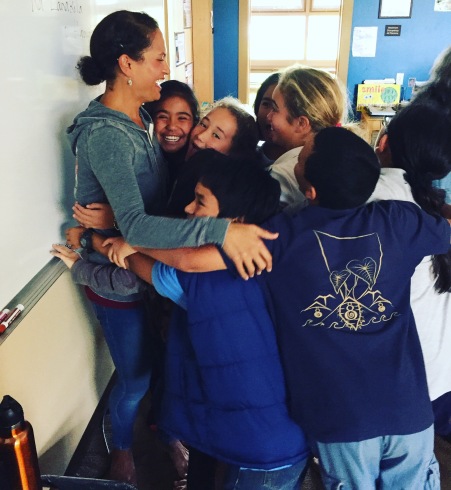

At Kanu o ka ʻĀina, with our kana o ka ʻāina, our natives of the land, the next generation.

Silence.

There is something to be said for silence, for the absence of sound, of words, of response. Silence carries meaning. It is never empty, never devoid of at least some significance.

My students taught me this. For in silence there can be ignorance, but there can also be consideration. There can be a mutual understanding and love, and in the case of one of my students, there can be a deep-seated sense of obligation and hope, one that does not always need words, one that does not always need sound.

A few weeks ago, in the last days of the trimester, after spending three months teaching a Pacific Studies course on art and activism in New Zealand, one of my students—a bright and bubbly girl from the islands of Tuvalu—rendered us silent when she stood in front of the class and asked, “What happens when you don’t have land? What happens then?”

We had spent time talking about environmental activism, considering those who stand to protect ʻāina, to protect land as a means of guarding and maintaining our sources of physical, spiritual, cultural, intellectual, and emotional sustenance and nourishment. And as I encouraged them to think about our own attachments to place, as islanders from homelands spanning our great Oceania—from the islands Fiji, to Tonga, to Tokelau, to Tuvalu, to Samoa, to the Cook Islands, to Aotearoa, to Hawaiʻi—I had neglected to consider her question.

So, in an uncharacteristic moment for her—a student who has not allowed the realities of life to crush to her optimism and joy, or her constant laughter—she stood in front of the class, stared directly ahead and said again, “What happens when you have no land, no base?”

You see, she is from Tuvalu, one of the groups of islands in the Pacific most vulnerable to the disastrous impacts of climate change, and in particular, rising sea levels. In fact, it is predicted that if current trends continue that Tuvalu will be one of the first nations in the world—along with Kiribati and the Marshall Islands—to be swallowed by the sea.

Thus, unlike those of us here who talk about land being taken by governments, by organizations, by greed, she was speaking quite literally about land lost, or perhaps land taken back to the ocean from which it came. “What happens then?” she pleaded.

Silence.

All I could do, in that moment, was offer her my silence. I could not pretend to understand the weight of her question, to consider the day when she and her family become permanent residents of another country—the first climate change refugees—with no land to return to, no land to plant themselves upon, no land to ground their identities in. Therefore, I could not attempt to craft a mundane or scientific response for the sake of response. And I could not offer words for the sake of words, for the sake of filling the silence.

No.

All I could give her was my silent acknowledgement of her struggle, or our human struggle, and my hope. She didn’t need my words, and more than that, she didn’t even need my tears. She needed my strength. And I gave that to her in my silence, while also making a vow to never let that silence be misconstrued or mistaken as consent.

You see our world is far too silent about far too many things, and that silence carries meaning.

Now you may be asking yourself, what does this have to do with Kanu o ka ʻĀina?

The name of our school comes from an ʻōlelo noʻeau, an old proverb that states, “Kalo kanu o ka ʻāina.” Translated, it means, “Taro planted on the land.” But metaphorically, it refers to us, to kānaka maoli, as being the kalo, as being natives of the land, who have been planted on the land, for generations.

What this school taught me, and what it continues to teach its students, is how to be a kanu o ka ʻāina, a native of the land, in the 21st century. And at the core of this identity is kuleana, or responsibility to ʻāina.

But I had never considered, not until that moment, as I looked into the eyes of my student, what it could mean to be a kanu o ka ʻāina in the absence of ʻāina.

And that’s when I realized: this is plight of indigenous people.

We live in a world that makes every attempt to marginalize us, to push us to the side, to silence our hopes, our dreams, and perhaps worst of all, our belief in our histories, in our stories, in ourselves.

Thus I reflected, and as I did so, her question haunted me, returning to me over and over again, as I thought about my own attachments to place, my own sense of responsibility, my own loyalties to ʻāina. Then one night, as I sat down to write her a response and to finally fill my previous silence with more than just hope and love, with more just than a shot at mundane or scientific fact, but with an earnest attempt to make sense of her struggle—of our struggle—I remembered an essay I once read, called “On Being Indigenous” and decided to share it with her.

In this essay, psychologist Michael Chandler (2013) asks: “How are indigenous persons meant to understand themselves, and instruct their children, in a world no longer willing to make a place for them? As country and country foods grow more inaccessible, as indigenous languages go extinct, as songs and stories and rituals are forgotten, as once traditional ways of dress become increasingly ersatz and costume-like and as cultural icons (once symbolic of a whole way of life) grow increasingly commercialized and Hollywoodized, how are indigenous persons to locate or to put into words and actions whatever constitutes the gravitational center of their own persistent indigeneity?” (p. 86)

Her homeland, with a population of around 10,000, is often considered so small in comparison to the rest of the world, so remote, so isolated, and so limited, that they fall off the radar, or in this case, they sink beneath the surface of what we choose to pay attention to. Thus, they live in a world that is too preoccupied to care about the impacts of a human-created catastrophe.

That’s when it dawned on me, whether it is through trying to replace temples with telescopes, or to poison waters with pipelines, or as one of our presidential candidates has done, trying to dismiss the realities of climate change, even while it threatens the existence of whole homelands, our ʻāina is littered (quite literally) with examples of such attempted erasure, physically and culturally.

But in the end, as the Prime Minister of Tuvalu once reminded us, “There are no boundaries to the effects of climate change” (ABC, 2014). Thus, what is happening there—as shorelines are washed away and lands are flooded, as soils and freshwaters are salinized, and as islanders stand ankle-deep on ʻāina now covered by ocean—will one day happen here, and everywhere. Therefore, to care about and to act on such issues is not just about saving some lives, but about saving all of humanity.

And it starts with kuleana, with being taught in a way that nurtures a sense of responsibility to ʻāina, filling silence with hope and action. That is what this school does.

At the end of her presentation, my student looked at the class, and with her usual smile, said quite nonchalantly for the occasion, “People call Tuvalu ‘The Sinking Island.’ But we are still here.”

And the reality is that they will continue to be, with or without their base. But that does not allow for complacency. In fact, our task now is to ensure that we save what we can while we can and that we work towards maintaining spaces—both physically and ideologically—in which we can continue to be indigenous, in which we can continue to understand ourselves and to instruct our children in ways that are distinctly our own, or as Chandler said, in which we can put words and actions to what is considered to be the gravitational center of our own persistent indigenetity.

Persistent Indigenetity.

That is what I learned from my student. And that is what I now carry for all of us: my persistence in being indigenous.

Rather than surrender to what some would believe is their inevitable fate, their inevitable doom, my student carries hope. Some may call her hope radical, for she looks to a future that she believes can and will be better than today, despite every attempt that this world has made to show her different.

And that is something I refuse to be silence about. In fact, it is that persistence that I choose to celebrate.

Why?

Because silence can be and often is misconstrued as consent of injustice, or as disregard and dismissal. And I’d rather spend my time creating spaces for our continued existence, here and everywhere.

My student, in her optimism despite all odds, reconfirmed and validated a lesson that I learned here, at this school, many years ago.

Our kuleana, or our responsibility as kanu o ka ʻāina is to ensure that there will always be a space for us, that when the world pushes, that we push back, and do not simply resist, but insist upon our place! This means sharing, this means speaking, this means singing and chanting, or writing and choreographing. This means creating and constructing; this means stomping and crying and praying when we need to because to do so is to fill the silence with dreams and hopes, with belief.

To do so is to fill the silence with love.

“Love,” as one of my students once said, “is a political act” against a world that teaches us to not love ourselves, our history, our values and beliefs, our skin color, our ancestors.

This is why I maintain, whole-heartedly, that Kanu o ka ʻĀina is not simply a “school of choice,” as it is often called, or a school that students can choose as an option, or an alternative, or an exception to the rule. Rather, I believe that Kanu o ka ʻĀina is a “school of necessity.” We need it because we live in a world that will continue to take our spaces if we are not willing to create them, to save them, and to nurture them for our future now.

Here, at Kanu o ka ʻĀina, when children sing the songs that tell our history, they create and save our space for singing. When they dance the dances of our ancestors, they create and save our space for dancing. When they speak our language, they create and maintain our space (and our right) to do so, now and forever. And when they write, think, and articulate their own existence, they let the world know that our lives matter, that our cultures matter, that our histories matter, and that they always did!

When we move and act, dance, chant, and sing with that truth, or with the knowing that our world is better because of the spaces that indigenous peoples hold, then we know that this school is far more than just “culturally-based.” It is a school of persistent indigeneity because our survival as a human race depends on such persistence.

Kanu o ka ʻāina is not about teaching culture, but about creating culture, a culture based firmly in our pasts, but responding to and acting for the needs of today. This school is about responsibility to ʻāina, not just for us, but for all of humanity.

You see our ancestors understood how to act with the ʻāina, and those islanders in the Pacific, on islands like Tuvalu, who continue to live lives of subsistence, understand this still. And yet they are the ones most at risk: our teachers, our elders, the ones with the knowledge of how to be true kanu o ka ʻāina.

Thus, we cannot be content with words for words sake, with action for actions sake, with mundane attempts at filling silence for the sake of being heard.

We must only be content with space, with a place for us to forever be kanu o ka ʻāina, to be indigenous, to be native, to be the ancestors that our children and our grandchildren will get to look to in a world that we have opened and freed for them.

That is kanu o ka ʻāina.

Mahalo.

References:

ABC (Producer). (2014, 31 Oct.). Tuvalu Prime Minister Enele Sopoanga says climate change ‘like a weapon of mass destruction’. [Web article] Retrieved from http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-08-15/an-tuvalu-president-is-climate-change-27like-a-weapon-of-mass-/5672696

Chandler, M. J. (2013). On being indigenous: An essay on the hermeneutics of ‘cultural identity’. Human Development, 56(2), 83-97.